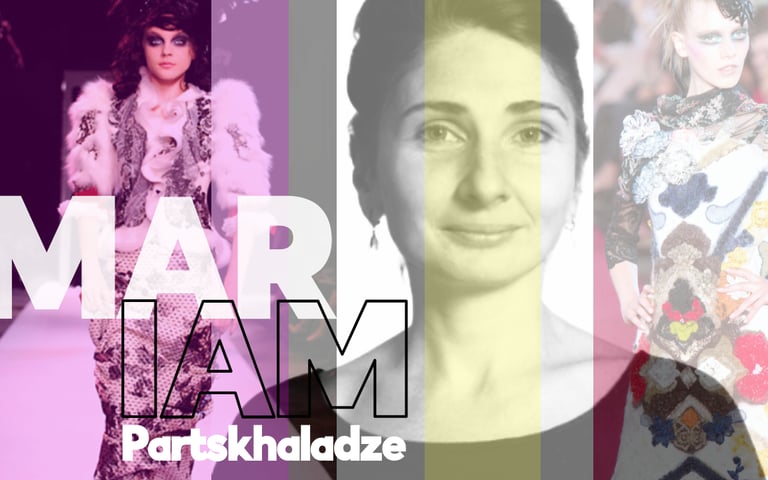

The Transformative Touch of Mariam Partskhaladze

From Caucasus peaks to Parisian runways, ancient felt finds its contemporary voice. Mariam Partskhaladze has spun magic for Christian Lacroix, Jimmy Choo, and a constellation of other high-end brands.

Elizabeth Lotz

Our wardrobes have become, in the words of fashion theorist Elizabeth Wissinger, a "laboratory of disposability." The fashion industry has built a machine for consumption. The promise is self-expression through style, values, identity, and aspiration. In reality, we are feeding a system that converts cultural heritage into quarterly profits while logging every purchase we make.

This machine thrives on what economists call planned obsolescence. The quicker garments fall apart or lose relevance, the more often we are compelled to buy new ones. Eventually, it becomes more profitable not to make anything that lasts. Why create something lasting when the system is designed to turn tradition into trash? It is a consumption engine built to manipulate us through artificial scarcity and manufactured desire. The techniques are close to those of Edward Bernays, who used psychology to steer public behavior. In this model, we are not consumers. We are users, in every sense of the word.

The Anomaly in the Machine

In 2003, Georgian textile designer Mariam Partskhaladze traveled into the Caucasus Mountains and encountered a profound knowledge system—one shaped by centuries of practice and quiet refinement. She found people who still held knowledge about how to make things that endure. She was not searching for an alternative to industrial production. She was simply exploring. Yet what she encountered in the daily practices of mountain communities directly contradicted the idea that mass production represents progress.

These communities had refined the art of felt-making over thousands of years. It was not quaint. It was essential for survival. Their process relied on human judgment, including the ability to sense when to stop, adjust, or change course mid-process. This kind of sensitivity is nearly impossible to replicate through machines or standardized systems. Their understanding of fiber behavior carried an intuitive precision. In many ways, it anticipated what modern material science would only later articulate. Industrial processes can imitate some results, but not without sacrificing essential qualities. Felt is particularly resistant to duplication. Machines often trade softness for strength, or breathability for durability. Traditional techniques were able to maintain these properties in balance.

What Mariam witnessed was cultural knowledge encoded with technical logic. In contrast, industrial production appeared crude rather than advanced.

The Economics of Subversion

From her atelier in the Drôme mountains of France, Mariam has accomplished something the fashion system insists cannot be done. She has made traditional craft financially viable without allowing it to be hollowed out by machinery. Her clients include Christian Lacroix, Jimmy Choo, Christophe Josse, and the Opéra de Paris. These partnerships do not reflect surrender to the mainstream. Instead, they represent a deliberate form of participation that challenges industry myths about what is practical, efficient, or inevitable.

Her collaboration with Christian Lacroix brought hand-felting into haute couture, where the word innovation often signals the replacement of craftsmanship with software. With Jimmy Choo, she contributed to the design of accessories, drawing on the tactile strength and subtlety that define her material sensibility, even outside the realm of textile. These qualities do not come from programming. They arise from human touch. When the Opéra de Paris commissioned her work, it placed its trust in the idea that hands, not machines, still hold a certain authority.

The Knowledge They Cannot Automate

The felt-making tradition in Georgia depends on delicate control of heat, pressure, and timing. These are not abstract variables. Too much heat will ruin the wool. Too little pressure and the fibers will never bond. Mass production cannot account for this kind of nuance. Algorithms are not equipped to listen to the material.

Mariam often incorporates older materials into her work, including lace, silk, and embroidery. Each commission requires its own mix of durability, texture, and structure. She achieves these outcomes through variation. It is an active continuation of a living science based on skilled labor. Her work quietly demonstrates how limited industrial processes truly are.

The Conspiracy of Preservation

Since the Saint-Étienne Design Biennale in 2006, Mariam has collaborated closely with Georgian embroiderer Nâna Metreveli. Their partnership shows that cultural knowledge is best preserved through ongoing dialogue across generations. It does not survive through individual resistance alone.

Metreveli’s embroidery carries religious and cultural symbols that commercial markets cannot easily absorb. Mariam’s felt provides structural grounding. Metreveli’s stitching adds narrative weight. What they create together proves that preservation is not passive. It requires daily, deliberate work that resists being streamlined or optimized.

The Touch They Cannot Synthesize

In an age of digital production, felt offers something that synthetic materials are designed to erase. It contains texture and tactility that can only emerge through human effort. Designers who work with Mariam gain access to properties no machine can replicate. At the same time, the ecological cost of synthetic materials becomes increasingly difficult to ignore. Chemical processing, energy waste, and rapid obsolescence reveal just how destructive efficiency can be.

Felt-making demands little energy. It relies on renewable resources. It produces goods meant to endure across decades, not seasons. This is a form of refusal. It upholds practices that industrial systems would rather eliminate. What we often call progress, with its drive for speed, low cost, and disposability, may actually be a system built to erode meaning. It wears down craft, culture, memory, and skill.

DecaDialogue: Ten Questions, One Artisan

In this recurring series, we explore the spaces where tradition survives mechanization.

Q. Your practice is rooted in the ancient art of Georgian felt-making, yet your designs feel deeply contemporary. How does working with such a historic technique influence your sense of creative possibility today?

A. Since early childhood, I have been passionate about fashion, fabrics, and I question their various manufacturing techniques and their history. In 2003, I discovered the ancestral method of felt-making. This technique became my preferred means of expression. Felt, while being a raw, primitive support, is also a material that offers richness and freedom of creation. It lends itself well to artistic expression and opens possibilities for contemporary creation. For this reason, I always seek to enrich my work by transposing other creative techniques onto this material.

I work a lot with transparent or openwork supports, combining different textures, embedding other animal or plant fibers into the wool, pieces of fabric, cut parts, sewn or molded in the mass. This marriage of an ancestral technique with modern materials allows me to access original aesthetic innovations. I try thus to show how, from the coarsest material—simple sheep’s wool—and primary colors, one can create infinitely feminine and delicate objects. Sometimes I feel like I am weaving, painting, and sculpting all at once.

Q. Do you find that your most original ideas emerge through intuitive, tactile exploration, or do they begin with a clear mental image that you consciously shape into form?

A. I am more tactile. A small piece of fabric catches my eye: colors, a pattern, the design of a lace scrap, all these textile treasures, which tell a story, are my sources of inspiration. Of course, there is nature, a book, a film, a meeting, or an event.

Q. Your pieces often appear to emerge organically, yet they serve precise aesthetic and functional roles. How do you navigate the balance between improvisation and control in your creative process?

A. Before starting a piece, I often make small samples to see how the materials react to felting. I calculate the shrinkage. And while making the piece, I observe regularly, adjust, and measure step by step until drying.

Q. Many artists describe constraints as either a cage or a catalyst. How do boundaries, such as working within a tradition or for a specific client, shape the way you innovate with fabric and form?

A. Participating in collections or live performances is a constant enrichment. Guided by the spirit of each collection or performance, but also carried by a tremendous wind of freedom, I find myself in a perpetual search for creativity with each new collaboration. Working with other designers, couturiers, stylists, or costume-makers pushes me toward other artistic discoveries. Seeing the result, at fashion shows, exhibitions, or performances, represents a magnificent reward for me.

Q. You’ve collaborated with major fashion houses like Christian Lacroix and Christophe Josse. How does the creative dialogue in collaboration differ from when you create independently?

A. When I create for them, I feel like I step into their skin and see through their eyes. I like being guided by a few reference points, the spirit of the collection, colors, while still having the freedom to create. I also really enjoy the exchanges between us! For my own projects, I follow my intuition and my ideas.

Q. Working with your hands, especially with a medium as ancient and sensory as felt, must create a deep emotional connection. Do you consider your emotional state part of the “material” you work with?

A. Both. It depends on the situation. Events that touch me, joy, sadness, and anger, are transformed into creation.

Q. Cultural identity seems central to your work, not just in technique, but in spirit. How has your Georgian heritage evolved within you as a creative force, especially while living and working in France?

A. I navigate between two worlds and take the best from both.

Q. Do you see the act of making as a kind of meditative or psychological practice? What inner states tend to accompany your most fulfilling periods of creativity?

A. Both. It depends on the situation. Events that touch me—joy, sadness, anger—are transformed into creation.

Q. Is there a creative decision or turning point in your journey that didn’t feel rational at the time but proved essential in shaping your voice as an artist?

A. Between 2008 and 2010, I did a training in haute couture embroidery, which fascinated me a lot, and since then, I have navigated between these two techniques.

Q. If you could leave behind one idea, not an object, but a truth, about the nature of creativity, what would you want future generations of makers to understand?

A. Creation is life. To be oneself.

From the mountain villages of Georgia to the ateliers of Paris, Mariam Partskhaladze reveals that the system we are told is unshakable may, in fact, be hollow. Advancement might sometimes look like regression. Efficiency might disguise waste. Innovation might destroy the very knowledge it claims to improve. Resistance is not something that waits for permission. It is already present in the hands that continue to create.