Kathryn of the Red Door & the Scribble Stitch

The Politics of Thread: How Ordinary Materials Tell Extraordinary Stories

Elizabeth Lotz

“Scribble Stitch” and “Kathryn Harmer Fox” sound like names plucked right out of a gilded storybook tucked inside a surrealist armoire. From her seaside studio in East London, South Africa, Kathryn Harmer Fox has developed what might be called a forensic approach to textile art: dissecting the familiar mediums of cloth and fiber to uncover their narrative possibilities.

A self-taught multimedia artist, her work refuses to sit politely in a frame or be filed under “fiber arts.” It insists, with audacious rigor, that thread and fabric can serve as probing instruments of cultural critique.

With her work exhibited across Europe, Japan, the United States, the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia, she brings a teaching philosophy as tactile as her materials, pushing machine embroidery to its conceptual and technical limits.

The Making of a Mind

Her beginnings resemble a case study in attention itself. Influenced by the African wilderness and the precision of a seamstress mother, she developed what theorists might call spatial and manual intelligence. Birdseed pincushions and animal sketches shaped this tactile, observant mind attuned to form and motion.

Initially set on becoming a veterinarian, Kathryn was instead drawn to the arts by the ordinary: unwashed wool, driftwood, and even the curve of her own hands served as inspiration. Through methodical experimentation, she has forged a dialect where the mechanical becomes insurgent, driving into memory, anatomy, and story.

The Dialect of Unruly Fibers

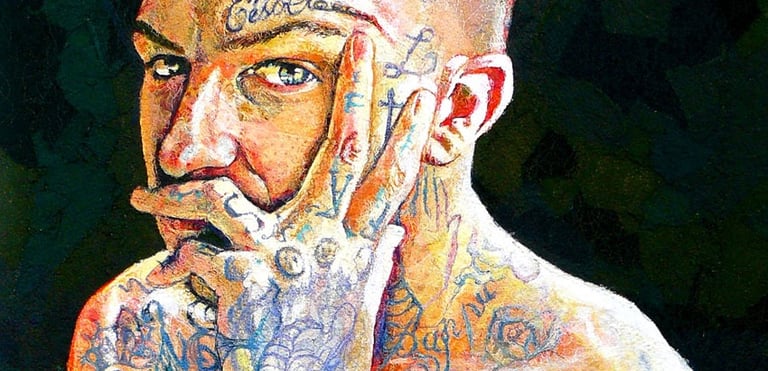

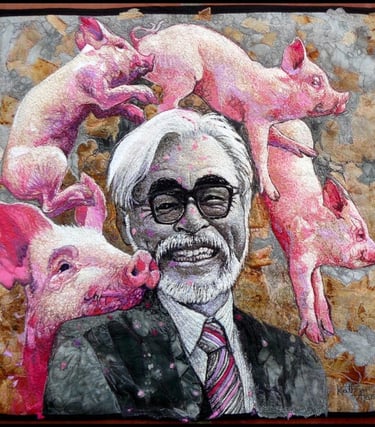

She’s counted among the world’s top fiber artists, a distinction claimed through her singular style. The Scribble Stitch is an expressive form of free-motion embroidery that brings portraits, botanicals, and animals to life with uncanny intimacy.

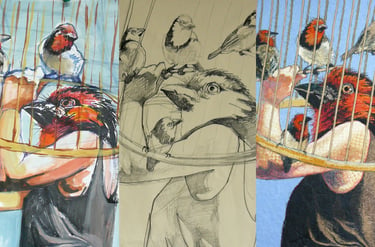

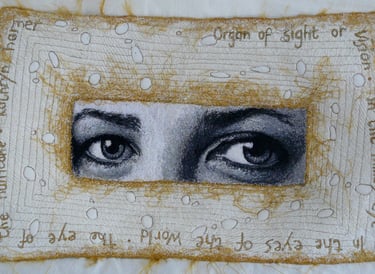

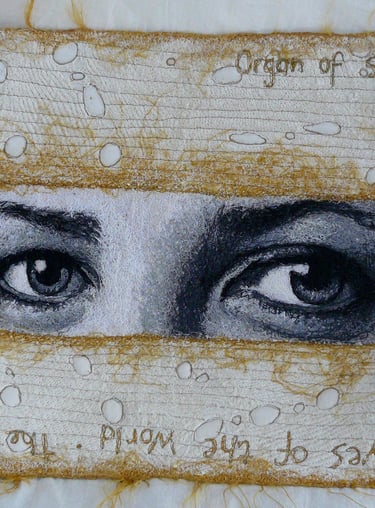

The method is deliberate, operating both as a visual language and a conceptual framework. Her process “draws” with thread, fusing emotional depth and figurative precision in a medium often mistaken for decorative abstraction. Starting with pencil sketches or photographic references (a method that suggests careful planning despite the "scribble" nomenclature), she constructs each piece through a multitude of materials. Each composition is a layered, tactile surface where every fiber functions as a mark and a meaning. Works like Birds on a Platter, inspired by her garden’s avian visitors, stare back and hold a gaze that blurs the boundary between observer and observed.

From Residue to Narrative

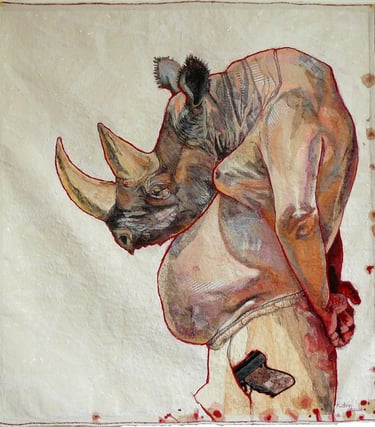

Kathryn wields thread, tea bags, unwashed wool, animal hides, and foil packaging to collapse the distinction between medium and message, exposing the fiction of permanence over story.

In her studio, high tables draped with fabric and a cadmium red door frame an assembly where her lexicon of fiber is anything but subtle; it’s structural, confrontational, and attuned to conservation, mortality, and emotional rupture. Using Life to Clothe Me in Death, channeling kimono silhouettes, wrestles with the finitude of life. Release, featured in Under the Milkwood, depicts emotional catharsis through pure motion. Other pieces, such as Hang Your Head in Shame and Fibre Platter with Ilse’s Eyes, probe human vulnerability, while The Egyptian Goose Family and A Bowlful of Birds celebrate the natural world.

To call her materials “unconventional” misses their intent. Each is chosen for its residue, history, and weight. From the physical to the psychological, through the environment itself, all conspire to recycle trauma, love, and decay. Her aesthetic is not eco-friendly; it’s eco-reckoning, proof that textile art can effectively carry psychological weight.

Artful Philosophy

She carries her teachings across continents, cultivating not rigid methods but a sensibility rooted in gesture and instinct. “Drawing skills are not necessary,” she insists.

Drawing from Betty Edwards' Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain (a text that itself challenges conventional art education), she argues that creativity emerges from gesture and intuition rather than technical perfectionism. Her motto, "Unless it is begun, it will never be done," functions as both practical advice and philosophical stance: imperfection is a guiding principle. “Never be afraid of failure,” she says. “Embrace her, for she is your greatest teacher.”

Kathryn works to make memory visible, insisting it remain unrefined and alive.

DecaDialogue: Ten questions. One artist. A thousand unravelings.

In this recurring series, we pose ten questions; always the same shape, never the same answers. More excavation than interview.

Q. You’ve said that “the ability to draw frees you as an artist.” How does sketching—whether on canvas or sand—bypass conscious planning and unlock raw ideas? Does drawing feel like a form of release, allowing insight before words or logic take hold?

A. I would say that sketching, like storytelling, uncovers the subject matter. Drawn marks expose the storyline when they are used as a preliminary practice and can be so enticing that they become the focal point of the artwork when fully explored. The way you have put it is perfect: to "bypass conscious planning" and "unlock raw ideas" is exactly what sketching does; it is the action of sketching that exposes the path forward.

Q. You grew up watching your mother sew; her breast sacks after surgery, her garments, her rhythms. How do these deeply personal tactile memories influence your work? When stitching, do you feel fabrics carry emotional residue that your hands instinctively respond to?

A. One of the most attractive aspects of this medium as an art form is its tactility. Materials that have lain directly against the skin of others (2nd hand clothing) or passed under the hands of another maker (the offcuts from a dressmaker) do carry a residue, a memory, even if it is only known to me, the maker.

One of my pieces, entitled Looking Forward into the Past, a portrait of my mother-in-law, is made mostly from clothing bought in a hospice; her face is made from "dead people's clothing". There is a wonderful patina to worn sheets or old, loved pyjamas, just right for interpreting faded eyes and grey hair. Yes, I definitely feel that fabrics carry emotional residue; a friend of mine dashed about draping old, discarded wedding dresses over her beloved cacti when an icy, cold front of killing frost swept into her Gauteng garden one morning.

Can you imagine the emotional response you would have to a row of cacti dressed in satin and lace, sequins and diamante on a frosted, misty morning?

Q. Your embroidery feels like drawing with thread; fluid, instinctive, yet precise. How do you balance spontaneous decisions with the focus needed to shape complex forms? What mental or emotional state helps you stay in that improvisational flow?

A. Being an artist takes discipline, hard work, and relentlessness. Excellence is achieved by dogged repetition - that fluid, instinctive precision you talk of is achieved only after the hundredth exploration. Spontaneity is easy when you know where you're going. There are 3 stages to an art piece:

Covering the blank canvas (this part is just hard work for me).

Getting lost in pure making (neither time nor place is apparent; this is an absolute delight).

Completing the work (not always recognizable because I am lost in the glorious space of 2).

The artwork itself keeps you in that mental/emotional state of improvisational flow; it has a voice of its own, and I just have to listen.

Q. You've described wildlife as an “endless wonder.” When observing animals or plants in their natural settings, how do those impressions metabolize in your mind before they appear in thread? Do you first feel their energy emotionally, visually, or physically?

A. Whether it is an elephant swinging its great head from side to side, or a sunflower thrusting its muscular stem into the sky, or sunlight glinting off a snake's scaly torso. Wildlife is a wonder, and nature is utterly incredible. An artwork resides wherever your eye rests; it's just a matter of exploring the lines and shapes with pencil, pen, and paint on paper. Once the painted sketch is done, I transfer the image to canvas and begin the fabric and thread interpretation using my domestic sewing machine.

Q. You often work with discarded or unconventional materials: foil, teabags, and salvaged fabric. How do the embedded environmental or social stories in discarded materials shape what you make, not just how, but why?

A. If we all teach ourselves, or are taught, to make things, we will constantly be on the lookout for stuff that can be used in the making. We live in an age of insatiable consumerism, of mass marketing, of senseless packaging; so much is just thrown away. If we are able to alter and lengthen the lifespan of just some of that stuff, we are lightening the load. Turning old debris into new art is a great reason for making things. I am always excited by an old pile of fabric or a topple of discarded boxes; so many beautiful images/objects lie within those piles just waiting to be made.

Q. You’ve said that “all creativity is healing, like laughter.” As you slowly layer thread and form, does the process resolve something internal—grief, memory, joy—or does it instead bring those emotions into sharper focus?

A. A bloody good question: does it cover or does it expose? Is the layering a form of insular protection, or is the layering a form of dissection leading to exposure and knowledge? I think the act of creativity does both. Being creative, making something that didn't exist before, is healing and joyful. It is a natural and true process; everything is in constant motion, and we need to meet that motion to stay alive and healthy. Boredom is a form of stuckness; it is dead and sick, unnatural and wrong, and you cannot be bored and creative at the same time. We also need to get outside of ourselves, to stop being so self-aware, and any form of creativity takes us into a space where nothing besides the thing being created exists; we become unselfconscious and secondary to the thing.

Q. Your workshops encourage students to break free from rigid definitions of drawing and art. How have those experiences changed the way you see your own work? Have you witnessed transformations that reframe how you think about artistic worth or access?

A. I think the most damaging belief system is that only certain people can draw or that being an artist is based on a talent or a gift. Drawing, like reading, is a learnt skill and, like any other skill, it takes discipline, dedication, and repetition. Being an artist hones your observational skills; whether you are a representative or an abstract artist, you are still drawing/painting/stitching what you see. Whether your subject matter is outward or inward, you have to learn to trust what you see and then learn to translate that sight as honestly as possible through your chosen medium. I do not believe that everybody is an artist, but I do believe that everyone is creative. We constantly learn from each other, how to see, and from our chosen mediums.

Q. Your mixed-media works—fiber, paint, paper, clay—accumulate in layers like an archaeological dig. Do older layers speak to you as you build?

A. At first, creating an art piece is just hard work; it's a slog covering so much empty space, it takes a lot of doing. All the information is coming from me; I'm telling the paper/canvas what it needs: lathering the paint on the paper or pinning the fabric to the canvas. And then there is a shift, and I forget that I am there; it's almost as if the work takes on a voice of its own, it becomes easy; I merely have to listen. The artwork tells me what it needs, and I just do it. I lose all sense of time or place. I would say it's a form of meditation (my time of healing). This is when I have to be careful not to overwork the piece; I have to stop when it's done, step away when the story is told. Sometimes I don't listen, and before I know it, I've said too much!

Q. Your materials—shweshwe cloth, raw wool, driftwood—are deeply rooted in your South African environment. Yet your work resonates far beyond that. When creating, are you consciously translating local experience into universal form, or does that bridge emerge on its own?

A. I don't know, I've never really thought about this; how lovely that you feel it resonates beyond my own South Africanness (I do feel that I am very much a South African, I identify strongly with my country and am both very critical of it and deeply empathetic with it). To answer your question: the bridge emerges on its own. We take ourselves wherever we go, and while there are cultural differences from country to country, we are all human, and we are all seeking meaning and connection.

Q. When an idea “attacks” you, as you’ve described, what does it feel like? An image, a physical pull, a phrase, a mood? How do you catch and translate that initial energy into the layered, tactile language of your textile art?

A. It starts off as a thought, a fleeting idea, and this hangs around getting more and more insistent until I work with it. Sometimes it's just a glimpse of something; I would say that it's usually in picture form. I will research the thing, sketch it into a format, work it out in a painted drawing on paper, and then translate it into fabric and thread.

Kathryn’s words curl around memory, improvisation, and a kind of creative honesty that is both disarming and deeply affirming. Her work, and her way, remind us that slow creation is often the most profound truth-telling.

Consider contacting Kathyn Harmer Fox as an art project in itself:

https://www.facebook.com/kathryn.art

+27823507024

+27437374814