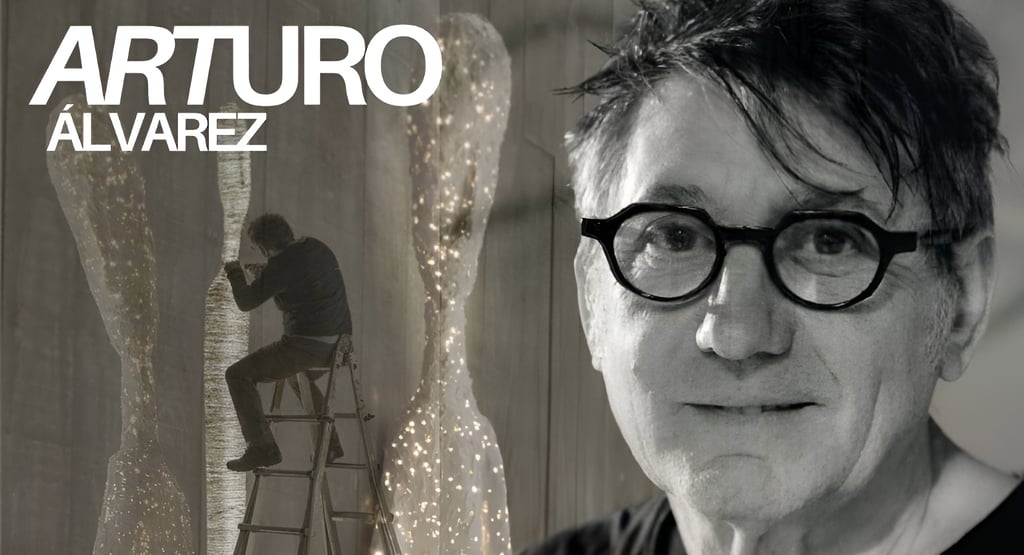

Arturo Álvarez and the Breathing Mesh

Light, you live with, not just see, because Arturo Álvarez gave it a mind and a heart

Elizabeth Lotz

The first time I saw his work, I mistook it for a memory I hadn’t had yet. It felt like standing inside a sentence I couldn’t finish. Some people chase the sun. Arturo chases the space in between where light meets shadow and emotion settles into material.

After more than two decades at the helm of his namesake lighting company, Álvarez threw down the gauntlet and plunged into something far less predictable: pure artistic exploration. As he later reflected in conversation, it wasn’t stepping away; it was stepping into feeling. This was a deliberate return to obsession, where light became less a function, more a state of being.

Today, Álvarez sculpts light, probing the charged psychology of human connection through its moods and gestures.

The Material Innovator’s Journey

Born in 1964 in A Estrada, a town in the province of Pontevedra, Álvarez made the kind of move that gives academic purists indigestion. He ignored the rulebook and the résumé polish and let the work speak. No art school, just obsession, and eventually, acclaim.

The root of Álvarez’s material genius was necessity, disguised as childhood ingenuity. He improvised toys from whatever materials his surroundings offered, turning scarcity into possibility. That inventiveness became his enduring drive; the urge to play, experiment, and create with whatever cooperated with his imagination. He never abandoned this impulse; it matured from childhood instinct into adult sophistication. This habit of resourcefulness taught him to think with his hands and push beyond conventional possibilities long before anyone mentioned design theory. It’s a mindset that instilled the ability to see potential where others see constraint, a pattern of perception that would eventually push the lighting industry to rethink what illumination could accomplish.

Álvarez’s grounding in craft evolved into technical mastery. From a vitral maker, he learned stained glass and Tiffany techniques; from carpenters, an understanding of how wood discloses its character. These influences gave his early lighting a structural clarity and elegance that leaned toward the future. In 2014, after two years of what can only be called material sedition, he unveiled SIMETECH®: a patented stainless steel mesh–silicone composite that behaves in ways that shouldn’t work, but absolutely do. SIMETECH® flows like liquid metal with a textile soul; a continuation of Álvarez’s earliest material manipulations. The material enabled organic, sculptural forms that felt more grown than designed.

That same year, the innovation earned him Interior Design magazine’s Best of Year — Innovative Translucent Shading/Lighting Solution award, solidifying his place as a designer. A tip of the hat to innovation. But more telling was what it confirmed: Álvarez doesn’t iterate, he rethinks. He rewires the system.

Innovation for Álvarez was never static. Concerned about the environmental impact of silicone, Álvarez sought a substitute that preserved the same appearance while being more eco-friendly. He adopted mesh coated with paint as a sustainable alternative. On a mission to upend the status quo, he proves that sustainability isn't a compromise, that sustainability and beauty can coexist. By embracing innovative materials and techniques that support ethical production and energy efficiency, he’s living proof you can have your sustainable cake and eat it too.. Psychologists would dub it value congruence: the rare thrill of your ethics and aesthetics finally pulling in the same direction.

But the drive to disrupt isn’t just about what he uses; it’s everything. Where most designers conform to what Roland Barthes might call the readerly material (the kind that behaves, signals, and explains), Álvarez reaches for the writerly form: a surface that resists ease, that speaks back, that invites the viewer to receive and interpret.

Global Reach and Emotional Resonance

Álvarez’s current work reimagines light as a medium for human experience rather than utility. The subtle tension in their forms reflects the ebb and flow of human relationships in a dialogue of light and shadow. Form, feeling, and then flicker; in that order.

This is a jailbreak from product to pulse.

SIMETECH® remains an essential inflection in Álvarez’s oeuvre, marking the point where material innovation became inseparable from artistic identity. The tension it embodied, at once industrial and alive, rigid and pliant, endures as a signature of his ongoing practice. Though Álvarez sold his company in 2020 to dedicate himself entirely to art, he remains the author and designer of many earlier works that continue in production, reaching homes and institutions worldwide.

His work has penetrated cultural institutions and design fairs from Barcelona to Tokyo, proving that good ideas endure and still travel fast and far. The Bety lamp’s place in the permanent collection of Barcelona’s Museu del Disseny underscores Álvarez’s lasting impact.

Light as a Language

Álvarez’s approach flows naturally from an affective directness so clear it can’t be fabricated. His light doesn’t capture; it releases and opens an encounter. It demands a shift from passive seeing to active feeling, from consuming design to entering a space where creation listens as much as it performs.

His work unfolds across three interconnected phases. Early motifs took inspiration from nature (leaves, coral, shells), luminous forms that blurred boundaries between sculpture and utility. This gave way to a phase of geometric abstraction shaped by Bauhaus principles and structural rigor. Today, his focus is intimate: human relationships.

Álvarez treats design and art as a continuum. The precision honed in his commercial years now fuels a deeply personal sculptural practice, one that embraces complexity without losing sight of tonal integrity. He avoids the trap of over-intellectualizing empathy. Susan Sontag once wrote that photography is a kind of appropriation. Álvarez’s work resists that impulse entirely. This honesty is as much his medium as steel or glass.

Yet, emotional precision is still precision. In Álvarez’s hands, it remains lighting, just not the kind you can switch off. What began in circuitry has evolved into psychology. Filaments are simple. Real feeling, on the other hand, is the true frontier. It’s messy, unpredictable, and 100% analog. Álvarez refuses to outsource emotion, keeping the lights on in ways machines never will.

DecaDialogue: Ten Questions, One Sculptor

Arturo on bending mesh, shadows, and emotion.

Q. You began with glass and Tiffany techniques, then developed SIMETECH®. When you engage with a new material, does its potential emerge through tactile experimentation more than planning? How do your hands lead your mind in discovering form?

A. My hands have been fundamental throughout my career. I went from working with cold, flat material to gradually shaping metal mesh with my hands, starting with the material I developed, SIMETECH®. I needed to create volumes; I was tired of the limitations of flat glass. In my work, I don't use a computer to design; I have always loved playing with materials, textures, and seeing what that experimentation can create. I really like that from a cold and shapeless material I can create objects with soul, friendly shapes, and that even visually can be perceived as warm.

Q. Do you see light as a metaphor for opposing inner states, or is it something more abstract, an aesthetic force that resists language?

A. Interesting question, I think it's both, neither intentionally sought after, but it turns out that it's all in my head and even in my spirit... Creativity draws from many sources, and the expression of that is something almost magical even, especially for myself.

Q. You’ve likened light’s emotive power to music. When you’re developing a piece, how do you sense when its emotional register is “off” or “in tune”? Is there a somatic cue, like tension or release, that guides you toward completion?

A. Music has been with me since I was very young. I'm always listening to music, and it has a great influence on me, and I'm sure it also influences my work. And of course, I imagine that my moods influence what I do and the final result. I am a calm person, I think I am quite balanced, who lives in a rural environment of great natural beauty, and I have the impression that this is somehow perceived in my work.

Q. You’ve moved from figurative to geometric to relational forms. Were these shifts driven by inner psychological needs or external curiosity, and what signals the need for change?

A. The need for change is marked by the weariness of having spent 20 years making commercial lamps. I needed to get out of that tight corset; I needed to tell internal things that worried me and still worry me, such as the difficulties of human relationships. At that moment, I made a 180-degree turn, I abandoned and sold the lamp company, and founded a new company to make sculptures that express all the things that concern me, or to make my own readings on different subjects.

Q. Your latest sculptures translate human relationships into light and form. Do you perceive social energy visually, or do you convert feelings, like intimacy, distance, and vulnerability, into spatial rhythms? How does empathy translate into physical design?

A. I think I feel closer to translating intimacy, distance, vulnerability, and relationships into spatial rhythms. I don't know how to translate empathy into physical design. I sincerely believe that when it is expressed from the heart, from the love for all living beings, the respect for everything, in the end, it is expressed in some way. Authenticity cannot be faked because it shows.

Q. After 25 years of creating designs through your eponymous lighting company, you sold it to pursue pure art. What internal process allowed you to separate from something so emotionally invested? Did stepping away open up new mental or emotional space in your creative life?

A. Leaving the lamps did not cause me any trauma. I gave it up because I felt that cycle was over; I couldn't give any more of myself. I gave it up very easily. Opening up to new spaces, new languages, and ways of expressing myself filled me with happiness, serenity, and the knowledge that I am where I want to be and doing what I like.

Q. Your commitment to handmade creation is countercultural now. What draws you to shaping materials by hand when machines could replicate the process faster? How does this physical intimacy with your work change the creative outcome?

A. I am very aware of the machines, but they don't worry me. For example, every mask I make is made without a mould, i.e., they are all different. Could machines do this? Yes, maybe, but to put human emotions, gestures, or expressions on them, that would be a development that I don't see in the short term. The big question is: to what extent will a machine be able to express human emotions, feelings, sensations, or expressions...?

Q. You work across visual, tactile, spatial, and now emotional modalities. When multiple creative forces converge, how do you decide which to foreground? Is there a hierarchy—emotional clarity, material form, light quality—that helps anchor the process?

A. My work is highly intuitive. I don't work with a predetermined hierarchy; I simply look for a set of elements that coexist harmoniously, that express what I have in mind. Perhaps 30 years of work helps to unite all these aspects and for the result to be coherent.

Q. You've moved from functional lighting for spaces to intimate artistic sculptures. How do you reconcile private intention with public interpretation?

A. I believe that in the current stage of my work, people connect with the whole of what I want to express, and there are even those who make their own interpretations based on their cultural and social references, etc. The beauty of this is to launch something and for it to connect with people. I never really know what it is about each person. The point is to surprise or even move people, which gives me joy and satisfaction.

Q. Your light shapes daily human experience in Harvard, Spotify offices, and Michelin restaurants. How do you process the reality that your creative choices inform thousands of people's emotional states? Does this awareness feel like pressure or a source of deeper motivation?

A. It makes me happy if my work can move people. Now, whether there are many or few or in important or more intimate places, is something I never think about.

And so, while replication floods the world, the gestures woven into Álvarez’s work stay, thankfully, beyond reach.

The internet, however, is always within reach. For further inquiries about Arturo Álvarez’s art and sculptures:

Visit https://arturoalvarez.art/en/

Or follow him on Instagram at https://www.instagram.com/arturoalvarez.art/.